THE PRO VIRILI PARTE PAPERS

Issue 1

A Newsletter Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of B.U.S.

Highland Avenue circa 1910 with Rhodes Park to the left,

across from original B.U.S. school building.

Rhodes Park served as the B.U.S. playing field.

JUNE 15, 2022

By Amanda Davis

As part of the centennial celebration of Birmingham University School, The Altamont School has commissioned the production of a marker that will be erected through the sponsorship of the Jefferson County Historical Association. The marker will be visible from the south end of Rhodes Park, directly in front of the original 1925 Birmingham University School building at 1211 28th Street.

Captain Basil M. Parks,

First Headmaster of B.U.S.

The First Decade of Birmingham University School

(1922-1932)

While not incorporated until 1871, and unlike Atlanta, Chattanooga, or New Orleans, Birmingham was a “new-south city”. By the early 1920s, the iron and steel industries were booming and included numerous mills, foundries, mines, and fabricating plants. Other industries—including textiles, lumber, and machine tools—were also established at this time. In 1922, a group of Birmingham’s first industrial leaders recruited Basil Parks, a highly respected instructor at Marion Institute to provide a preparatory education for their sons focused on academic excellence, discipline, and honor. In addition to its emphasis on discipline, the school’s military flavor was apparent in many ways, one of which was the insistence of Headmaster Parks that teachers be referred to as “Captain,” pronounced “Cap’m” by the young southern gentlemen.

In reading about the early years of B.U.S., we see the strong influences of Marion Military Institute. In addition to Parks, second Headmaster, Captain Robert Louis Johnson also came from Marion in 1929 and remained there throughout the Depression and World War II years. In fact, classroom discipline was rarely a problem, as more than half of the faculty came to B.U.S. from Marion Institute. Teachers demanded strict attention to the day’s lessons and the boys responded appropriately.

The first B.U.S. school building as seen today. The first floor housed

offices and classrooms, while the second floor was home to

the auditorium, science lab, and library.

Sideview of the building as seen today. On the bottom floor can be seen the door to the bicycle room where boys entered every morning for class.

1926: The First Schoolhouse

For the first few years, the school did not have its own building but met on the upper floor of a building on Highland Avenue, which also housed Margaret Allen’s school for girls and the “Little Theater” troupe. As enrollment increased, the Birmingham University School purchased property near the corner of Highland Avenue and 28th Street. In 1925, construction of a new school building began at 1211 28th Street, South, known as Waucoma Street at that time. In early 1926, six male teachers and sixty-nine students moved into this clapboard school building, which was originally painted red. Annual tuition ranged from $200 to $300, or about the same price as a new Model T Ford.

Fortunately, Parks had placed B.U.S in an ideal location to be the “neighborhood school” for Birmingham’s most prominent families. Highland Avenue residents could either walk or ride their bicycles to school each day. The school was also within walking or biking distance of newly built homes on the Red Mountain crest with their spectacular views of the city below. Its location was convenient, also, for new suburbs just over Red Mountain in Shades Valley.

As one walks up the steps to the portico and enters the first-floor hallway, it is still easy to visualize the students of long-ago changing classes, laughing and taunting each other as boys and young men tend to do. To the right of the entrance are two stairways, one leading up and one leading down. On the top floor there was a library, an auditorium, and a laboratory. In the basement were showers, as well as a bicycle room, cloak room, lunchroom, and the heating plant.

Even though the original building currently houses office space, its façade—and many of its interior features— look much the same as old B.U.S. school photographs.

Little has changed in the interior stairwell of the building, 2022.

The Peters House as seen today, once the home of Captain Parks and his wife.

On the uphill end of the property was the Peters House at 1215 28th Street South, built in 1905, which became the home of Captain Parks and his wife. It was a clapboard house reminiscent of a Victorian shingle-style but with the distinctive pillars and terrace walls made of rocks. The restored Peters House is also a notable addition to the collection of homes of assorted styles which lie along the walking route for neighborhood residents around the three lovely parks on Highland Avenue—Caldwell, Rhodes, and Rushton.

Building the Boy: Rigor, Discipline, and Effort

Just like most school buildings, this new facility was a non-descript lap-siding structure, originally painted red. The main entrance on 28th was the only part of the structure that possessed even a small degree architectural distinction. Even so, what went on inside the building was unique. Students would arrive early in the morning—many of the boys rode their bicycles and would enter through the basement bicycle room. Before going upstairs, they would go to the cloak room, hang up their coats, and get books they needed. Captain Parks was especially proud of the modern steel lockers added in 1930 through the efforts of the B.U.S. mothers.

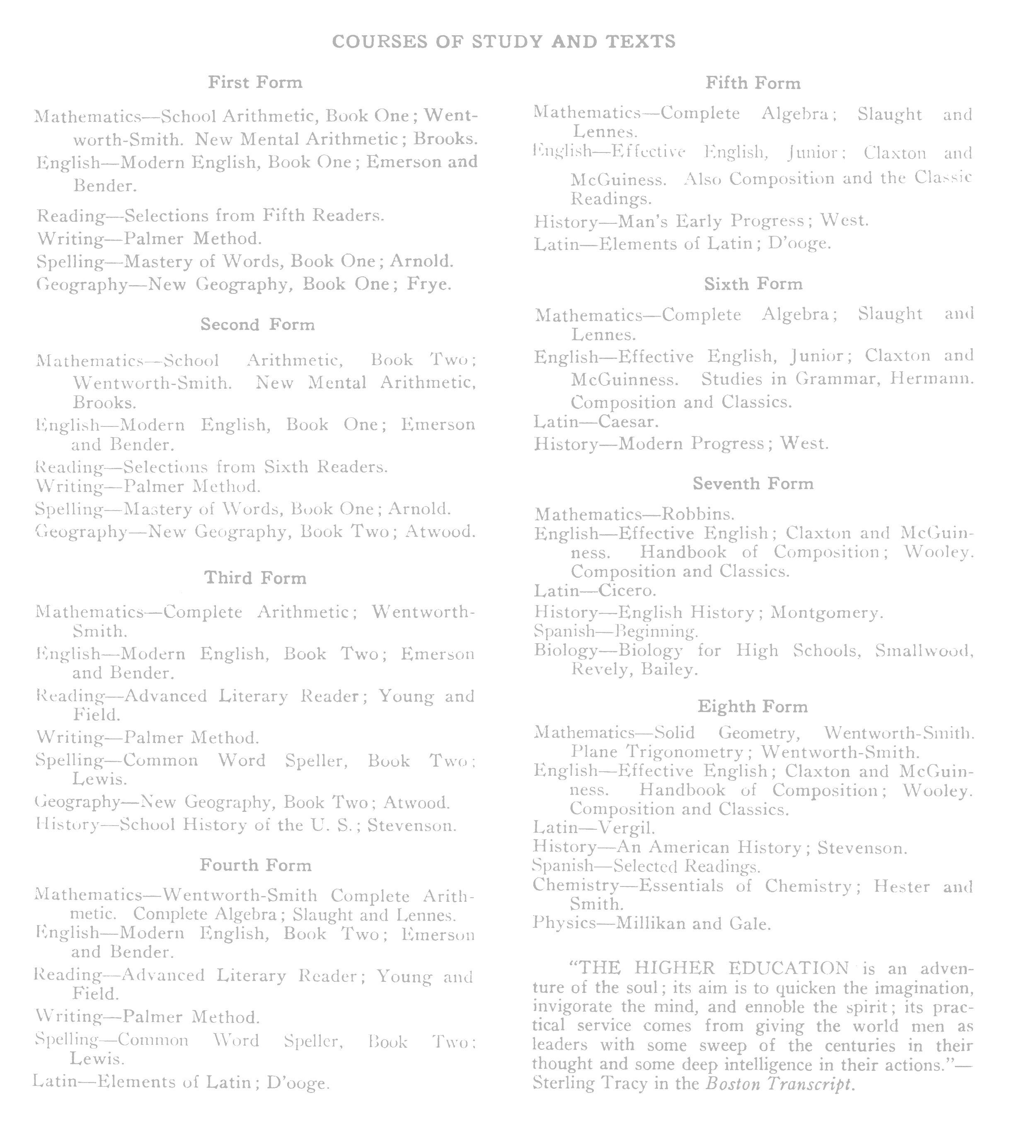

The overarching goal for Parks and his faculty was to offer the boys of Birmingham a thorough college preparatory education without them having to leave Birmingham to obtain it. The new school’s curriculum was classical and rigorous. Using the nomenclature common to English public schools and New England academies, B.U.S. organized its students into “forms” rather than grades. Interestingly enough, the eight forms described on the “Courses of Study and Texts” page of the 1925-26 B.U.S. handbook correspond to today’s Altamont structure of Lower School (grades 5-8) and Upper School (grades 9-12). Mathematics was the subject listed first in all eight forms. Then came English grammar, reading, writing, and spelling. The study of Latin began in the 4th form and continued through high school.

The rigorous mathematics instruction delivered by Parks included mental arithmetic competitions—he believed that being able to think quantitatively while standing on one’s feet would give the B.U.S. boys a step forward on their future educational paths and in life. B.U.S. alumni quoted in Chris Thomas’ 2010 book remember William Caldwell, Caldwell Marks, Pete Marzoni, and Joe Farley as frequent winners in these math competitions during their time at B.U.S. To attest to rigor in grammar, Pete McGriff, who attended BUS from 1929 to 1936, remembered having to diagram sentences that were a paragraph long. Other students remembered being required to define and spell arcane and difficult words found by their English teachers through microscopic examination of various classics. In addition, Captain Parks and his faculty believed training in public speaking was necessary for success in any field. Thus, all boys, were expected to deliver weekly speeches in the auditorium in front of the entire student body, regardless of form. The students chose the topics themselves while the faculty approved topics, judged the speeches, and selected winners.

Although class time was business-like, friendly conversations among both students and faculty took place in the downstairs and upstairs halls between classes. In addition to discipline in academic pursuits, the discipline of military-style physical fitness was taught and, as Rhodes Park was located just down-hill from the school, it soon became the athletic field. Each day Captain Parks would shout “Fifth Form Rise! About Face! March!” So, off the boys went to the park, walking in the military formation like a platoon of marines on parade. The daily program included calisthenics—sit-ups, push-ups, jumping-jacks, for example. For the annual competition, Captain Parks brought in local army officers who selected winners based on form and endurance.

Parks and his faculty required a considerable amount of daily effort from the students with the expectation that, with this practice, every student could succeed academically. Those whose lessons were “poorly prepared” were made to spend an extra hour at school each day correcting their mistakes. Students who were unable to complete their work during the week were made to attend school for half a day on Saturdays.

B.U.S. faculty members: Paul J. Benrimo, Robert A. Mickle, Wilmer D. Webb, James White, Newell C. Griffin, Basil M. Parks

“For those who have the ability and do not try, an hour after school is punishment. For those who do their best, the hour is for the purpose of giving them individual attention.”

The small numbers and faculty leadership created an educational experience far more individualized than a boarding school or a public high school. Expectations were high for every student, not just those at the top of the class.

Faculty at the time were men who served as teachers, friends, mentors, coaches, and sometimes, even, as drill sergeants. They preached daily sermons about their belief that every boy could complete a rigorous course of study and graduate. Furthermore, at B.U.S., the students in turn convinced each other that with effort anyone could win whether it be a mental arithmetic prize, an athletic competition, or the best speech of the week.

The Spirit of Fellowship and Teaching Excellence

“Here at B.U.S. the spirit of fellowship should, and we think does, reign supreme. In a small group such as this all our associates are our personal friends, and it will be upon them that more than anything else we look back. The friendships that we form here are among the most valuable things this school can give us. Later, much later, we will all look back and fervently bless our school for the friends it gave us.”

The school prospered throughout the 1920s and, during these early years, characteristics which would come to define B.U.S. were already well established. First was the “spirit of fellowship” described in Herbert Smith’s column in a 1931 edition of the school newspaper, the Omni-BUS. Within the small-school atmosphere described by Smith, then a teenager, students were a team, a band of brothers. Even so, the emphasis of Parks and his faculty on personal best taught them how to be competitive. In looking back, we can now imagine this team spirit as a prelude for B.U.S of the late 1960’s and early 1970s when Coach Phil Mulkey’s boys won an amazing number of state athletic titles—the abundance of which, for a school with fewer than 200 students, still ranks among the most impressive accomplishments in the history of Alabama high school athletics.

The second characteristic which has been present throughout the school’s 100-year history is teaching excellence. Teachers who are truly excellent have lofty expectations for every student, as well as themselves. Excellence means teaching to the top of the class and never “dumbing-down” anything. Additionally, truly excellent teachers always seek ways to reach every student, although all are in different places in their quests for knowledge.

Attendance in the late 1950s grew, so the Birmingham University School relocated to a larger campus on Montclair Road. Even so, throughout its history, B.U.S. remained relatively small. In 1975, B.U.S. merged with the Brooke Hill School for girls to become The Altamont School. One hundred years later, though many changes have taken place, the new school’s commitment to excellence in all things has never wavered from the original pledge made by B.U.S. faculty and students so many years ago.

Pro Virili Parte Today

Just inside the entry of The Altamont School hangs the Birmingham University School seal embossed with the motto Pro Virili Parte. This daily reminder of the earliest roots of Altamont is just one example of the inestimable debt we owe our forebears who, under the direction of Captain Basil Manly Parks, conceived of and created a new institution of learning for the young men of Birmingham. The exact translation of the motto, from Latin, reads as “for the manly part.” The phrase was an idiom from Cicero, which meant at the time “to the best of one’s abilities” and is often used in the original papers and correspondence related to the founding of the school, and for many years later. Pro Virili Parte is that it first appeared as the school’s motto in the early 1960’s when Hardie Perritt as Headmaster from 1959 until 1962, began requiring the boys to wear coats and ties. Thus, the need arose for a crest to go on the pocket of an official school blazer. Around the same time, Dr. Hubert Hill Harper, also a classical scholar, joined the school’s faculty as Upper School Director of Instruction. Frank Marshall, Headmaster from 1963 until 1968, recalled that it was Harper who chose the motto for the crest.

Today, Pro Virili Parte Papers seems an appropriate title for a newsletter for the B.U.S centennial celebration, because a 21st century vision for excellence in college preparatory education still flourishes on the Altamont campus, located within the city limits of Birmingham less than two miles from the original school building. Although the Altamont motto of “Truth, Knowledge, Honor” moves away from the gender-specific nature of Pro Virili Parte, members of the Altamont faculty and student body still strive to live out the Ciceronian ideal of doing everything to the best of one’s ability.