THE PRO VIRILI PARTE PAPERS

Issue 2

A Newsletter Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of B.U.S.

AUGUST 8, 2022

THE LEGACY OF CAPTAIN JOHNSON (1929-1945)

By Amanda Davis

Early on Monday morning, October 28, 1929, boys were bicycling and walking along Highland Avenue toward the B.U.S. school building for another week of studies. However, on that very same Monday morning, many miles away in New York City, events were unfolding that would change B.U.S., Birmingham, and the entire nation forever. Since the spring of 1928, stock prices had been rising steadily but fell dramatically on Friday, October 24. Despite the efforts of large national banks to turn things back around, on Monday the market crashed.

Captain Robert Louis Johnson

By the time the B.U.S. boys left school that day the Dow Jones Industrial Average had lost 13% of its value. Stock prices for U.S. Steel, the largest employer in Alabama, were 110 points below those of September 1928. From a peak enrollment of 78 students in 1926-27, just a few years later there were fewer than 50 students. When Franklin Roosevelt delivered his first inaugural address on March 4, 1933, the President described Birmingham as “the worst-hit town in the country.” Thus, Captain Parks was forced to let some of the faculty go, and others left of their own volition.

Even though B.U.S. suffered economic and faculty losses during the depression years, a big gain was the arrival of Captain Robert Louis Johnson. Born in Wetumpka, Alabama in 1896, Johnson enrolled in Marion Institute’s Army-Navy College at the age of 16. After successfully completing the program, he headed north to the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. But unfortunately, of necessity he left after only two years due to deteriorating eyesight. He returned to teach at Marion until the U.S. entered World War I, at which time he then enlisted in the army as a lieutenant.

However, just before the division left for France, his rank was elevated to captain and he was given command of his own company. After various post-war pursuits, he arrived in Birmingham in 1929 (at the age of 33) to teach math and physics at B.U.S.

Edward Rushton at the chalkboard, chalk in one hand and eraser in the other per Captain Johnson’s directions.

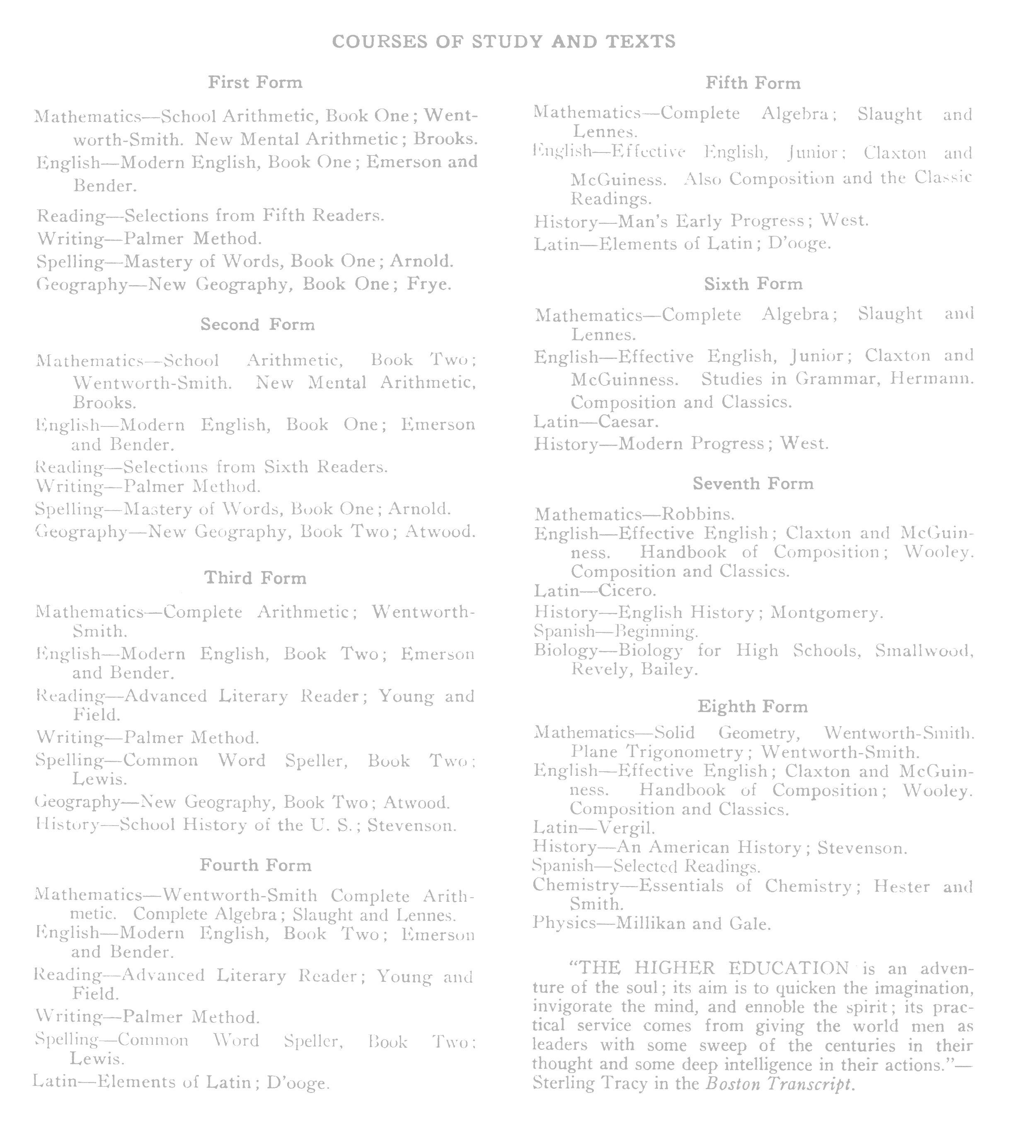

College Preparatory Mathematics

When Chris Thomas wrote his book about B.U.S. in 2010, he interviewed and/or corresponded with 15 or so of Johnson’s former students and every single one of them said he was among the best teachers, if not the best teacher, they ever had – in any subject, at any school and at any level – including professors at universities like Virginia, Princeton, and Yale. Johnson’s gifts in teaching mathematics were exceptional strong. Carrying on the practice introduced by Captain Parks, Johnson drilled his students daily in mental arithmetic and held frequent classroom competitions. For solving multi-step problems, the chalkboard became the teaching platform. Johnson taught the boys to write on the board with one hand and erase with the other, which today is a classic “sight-gag” about math. If a student made a mistake on blackboard work, Johnson would hurl a piece of chalk at the incorrect figures and yell something to the effect of “Keep your brain ahead of your chalk!” A former student, Hobart McWhorter, explained that he had a way of communicating with students “the big picture” of mathematics so that they understood it at a fundamental level. Johnson emphasized ingenuity rather than just using memorized procedures and would remind his students about the importance of estimating the answer. For those who made it through Captain Johnson’s exacting courses, college-level mathematics became much easier. Bill Matthews recalled that “he didn’t even have to crack a book in his freshman course at Georgia Tech.”

Challenging Exams

Johnson’s exams were notoriously challenging as we can see by looking at a copy of one of his hand-written exams preserved by Thad Holt and now a part of Altamont’s B.U.S. archives. Johnson was a stickler for following rules and honesty, both of which were expected of B.U.S. boys. Jimmy Shepherd recalls getting back an exam on which Johnson had given him credit for a wrong answer. Shepherd then pointed out to Johnson the mistake on his paper hoping Johnson would not lower his score – but no – 4 points off!

The small size of B.U.S. made it possible for Captain Johnson to emphasize personal best rather than competition. He praised students whose work showed effort and was most critical of those who did not try. Additionally, Johnson was not averse to capitalizing on teachable moments – even during tests. When walking around the classroom and seeing a mistake on a student’s test paper, he would tap him on the shoulder and say, “You might want to rethink that answer.”

Frequently, there was friendly competition between students, sometimes within a family. Allen Rushton remembered competition with his cousin, Billy Rushton, and that Billy was the usual winner. However, when Allen received a test grade of 96, he noticed that 4 points had been taken off – not because the answer was wrong but because the problem had not been worked in the prescribed way. Allen then showed Johnson his paper and explained that the computation was based on a “short cut,” which Johnson, himself, had told the class about earlier in the year. Allen was immediately re-awarded the deducted points, so, on that day, both Allen and Billy Rushton received perfect scores of 100.

Window Escapes

While he could be a harsh disciplinarian, Johnson’s students were quick to defend him as being fair. And, of course, corporal punishments under this leadership of army officers in the 1930s and 1940s was perfectly acceptable. Additionally, Johnson liked to incorporate a degree of sportsmanship into his discipline. If an offender could escape out one of the school’s first-floor windows, making the leap onto the alley adjacent to the school building, Johnson would grant him absolution. Woe be unto the student, however, who was not quick enough to make an escape. Caldwell Marks remembered one afternoon when his classmate, Tony Marzoni, was bending down over Johnson’s desk and they were talking about his math paper.

Marks was standing behind Marzoni, waiting in line to discuss his own paper with the captain. Marzoni’s position was just too inviting, and Marks stuck him in the rear end with a sharpened pencil. Marzoni poured forth a string of obscenities, so now both boys were in trouble. While Marks the instigator managed to escape, Johnson’s strong arms pulled poor Marzoni back inside the window where he was forced to accept his punishment.

Headmaster (1936-1945)

In 1936, Captain Johnson became headmaster when Basil Parks was called back into military service with the Army Corps of Engineers. The boys of the 1920s and early 1930s, the disciples of Parks, had moved ahead in their lives, but the B.U.S. boys of the late 1930s and early 1940s belonged to Captain Johnson. As James Simpson said, “Captain Johnson was not only the headmaster; he was its very soul, its personification.” Johnson’s reputation as a great math teacher brought new students to B.U.S. Thus, Johnson was able to hire new teachers and field the school’s first interscholastic athletic teams in basketball and football.

Neither the school’s first basketball team nor football team won many games. The basketball team participated in a league of 12- and 13-year-olds, which played their games on Saturdays at the Downtown YMCA. Captain recruited a Birmingham-Southern basketball player to teach the boys basic plays that enabled them to win a few games. Hobart McWhorter recounted in a past interview a story of their first football game, at the Mountain Brook athletic field on Cahaba Road, during which the player next to him was so nervous he vomited. Even so, these B.U.S. first teams always had the support of Captain Johnson cheering them at every game. After all, they were his boys – they loved him, and he loved them.

The World War II Years

During World War II, it was business as usual for the boys who had not graduated, but students did recount specific wartime memories. They were able to locate places American troops were going all over the globe – Tunisia, Salerno, Leyte, Luzon. Other students remember collecting scrap metal and rubber for the war effort and watching as military convoys made their way past the school on Highland Avenue.

The wartime gas rationing made a virtual “school bus” out of Jimmy Shepherd’s light blue Hudson. In the mornings, boys who lived near Shepherd would frequently pile in and pick up others along the way. Then, when he turned down 28th Street off Niazuma Avenue, Shepherd would coast down to the school to save fuel. Of those students from the 1920s and 1930s who had already graduated, most would serve in the armed forces in some capacity during the war. Lee “Pete” McGriff became a fighter pilot in the Navy. Bill Spencer and Peterson Marzoni served as officers in the Marines. Spencer, who was Pete McGriff’s classmate at B.U.S., participated in all five of the 2nd Marine Division’s major landings at Tarawa, Saipan, Okinawa, and Iheya Shima. Herbert Smith saw action with the U.S. Army in virtually every European campaign, and Elbert Jemison, Jr. served with Patton’s 3rd Army in northwest Europe. Caldwell Marks served on a destroyer in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, and participated in the capture of U-505 off the coast of Rio de Oro in June of 1944.

During the winter of 1944–1945, Allied troops were on their way to victory in Europe. But, back in Birmingham, January 2, 1945, was a cold, grim day. In anticipation of the boys’ return to school after the Christmas holidays, the school janitor Elijah Frazier came in early to fire up the boilers. When entered the basement, he saw Captain Johnson lying unconscious on the couch with a head wound and a .38 caliber revolver in his hand. He was rushed to Hillman Hospital but died in the early morning hours of January 3. There was speculation about the cause of Johnson’s death, but no one really knew what happened to their beloved teacher and headmaster. Thomas points out in his book that there was a history of depression and suicide in his family. Just as one would expect, he left his affairs in perfect order. He was buried in his hometown of Wetumpka, Alabama on January 6, 1945.

The First Quarter Century (1922-1947)

In the 1920s, the Birmingham University School started out strong with the superior leadership Basil Parks, but the 1930s brought on both enrollment and financial challenges. Due to the loss of their beloved headmaster and teacher, 1945-1947 proved to be difficult for all of those remaining at 1211 28th Street. In the fall of 1945, the boys who had been at B.U.S. during the last years of the Great Depression and World War II years, would now move on to the next chapter of their lives. Even so, Johnson’s legacy would remain in the hearts and minds of the boys he loved so dearly. Jimmy Shepherd would go to Virginia Military Academy at the age of sixteen. Billy Rushton, Allen Rushton, and Hobart McWhorter would distinguish themselves at Philips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, where they became known as “the math wizzes from Alabama.” Bill Matthews, whose grandfather J.T. Murfee was a founder of Marion Military Institute, would complete high school at Marion and then go on to Georgia Tech.

When considered as a unit, those first 25 years of the Birmingham University School could best be described as its “Marion Era.” Both Johnson and Parks had previously been on the faculty at Marion, and both leadership styles emphasized strict discipline, honor, personal fitness, and a rigorous course of study. The school building had no gym; thus military-style physical training took place with marching and calisthenics in Rhodes Park. Additionally, the two captains taught their “troops” – this band of brothers – that it takes effort, even for the most naturally gifted, to develop one’s abilities to the fullest. They also taught their troops how to be competitive in the outside world. The peak enrollment for the first quarter century in the life of the Birmingham University School was in 1927 with 78 students. In the 1930s enrollment dropped to 40 to 50 students. Even so, new developments of Cicero’s “Pro Virili Parte” ideal were yet to come.

The Second Quarter Century (1948-1972)

In 1954, in hopes of expanding the program and getting more students, a few of the school’s patrons purchased a narrow strip of land along Montclair Road for $12,500. At that time, the new location was also a fortunate one. It was still within walking distance of Redmont, English Village, and Forest Park, but less than a mile to the south, were the over-the-mountain neighborhoods of Mountain Brook and Crestline. The property was adjacent to Ramsay Park, which was utilized as a playground and athletic field. The move to the new facility brought with it a new era of great teaching in the humanities. Frank C. Marshall, Jr. arrived at B.U.S. as an English instructor in the fall of 1957. After receiving his bachelor’s degree at Birmingham-Southern, he taught for two years at Walker Junior College. Despite his soft-spoken demeanor, he was also an excellent public speaker. In 1961, Marshall completed a master’s degree at Birmingham-Southern while he was teaching full-time at B.U.S. His students quickly began to appreciate his intellectual ability, as well as his passion for literature and teaching.

Frank Marshall

Marshall became headmaster of B.U.S. in 1962, and one of his most fortunate hires, for the fall of 1964 was a 26-year-old graduate of Birmingham-Southern named Martin Hames. He was much more than a teacher – he was a force. He had an amazing ability to take even the most uninterested, disengaged student and create within the boy a passion for literature, history, and even the fine arts. Less than a year after his arrival he had convinced patrons to donate paintings to the school and hosted the school’s first “Town Hall Gallery” art show in February of 1965.

Coach Phillip Mulkey was another force that roared onto the B.U.S. campus in the early 1960s and, under his guidance, this relatively tiny school had won a record number of state athletic titles. Soon after he arrived, Mulkey became known as “Physical Phil” and created a model fitness program for every student, including push-ups, pull-ups, sit-ups, squats, as well as lots and lots of running. As Shuford White reminisced, “He gave you goals and built you into something more than you ever thought you could be.” White became a champion shot-putter under Mulkey’s leadership. Members of the Class of 1968 – Milton Bresler, Bruce Denson, Tom Huey, and Harry Moon – captured for B.U.S the 4th straight state title in track and field events.

As the first fifty years of Birmingham University School history came to an end, its students and faculty remember it as a truly great prep school, the whole of which equaled more than its parts. This remarkable culture reflected traditions that dated back to the era of the two captains – Parks and Johnson, and was continued by the Frank Marshall, Phil Mulkey, Martin Hames, and many others. Carl Adams, who had transferred to B.U.S. from Shades Valley, later commented, “Because of its size, there was an incredible interaction between students and faculty and a tendency to develop friendships between students and teachers that didn’t really exist anywhere else at the high school level. Every one of us was highly motivated; and thus, it became a contagious atmosphere. I believe that many of us reached well beyond our abilities because of that atmosphere.” And as Jim Palmer succinctly put it in the Afterword of Chris Thomas’s book, “It was an extraordinary place for a boy to become a man.”

The Next Fifty Years: The Altamont School

The last class graduated from B.U.S. in 1975, and many B.U.S. students at that time expressed sadness that their beloved and unique prep school would never be the same. But looking back from the perspective of this centennial celebration, this new school – with more students, more money, and more diversity – would remain a new close-knit community in which the sum was greater than its parts.

At the heart of this 100-year-old endeavor was teaching excellence. Teachers who are truly excellent and have high expectations for every student, as well as themselves. Excellence means teaching to the top of the class and never “dumbing-down” anything. Furthermore, truly excellent teachers always seek ways to reach every student, although all are in different places in their quests for knowledge. Therefore, each alumnus of B.U.S., as well each alumna of The Brooke Hill School (1940-2022) can be assured that a unique 21st century vision for excellence in college preparatory education still flourishes on the Altamont campus, located within the city limits of Birmingham less than two miles from the original B.U.S. building. Although the Altamont motto—“Truth, Knowledge, Honor”—moves away from the gender-specific nature of Pro Virili Parte, members of the Altamont faculty and student body still strive to live out the Ciceronian ideal of doing everything to the best of one’s ability.